WORD NEWS

White gold from Black palms: the Gullah Geechee combat for a legacy after slavery | Slavery

Dorcas, who was 17 and picked Sea Island cotton, bought for $1,200. Cassander, a 35-year-old “prime lady” who additionally picked cotton however was susceptible to “matches”, bought for “simply” $400. The identical worth was paid for Emiline, 19, who was described as a “prime younger lady cotton hand”, and Judy, who was solely 11.

Beneath torrential rains, on 2 and three March 1859, these enslaved Africans, who labored on rice and cotton plantations within the Sea Islands of Georgia, had been bought on the Ten Broeck racecourse in Savannah. One witness to the sale wrote that the climate was so “violent” that it felt as if the skies had opened and wept. That’s how this occasion, the most important public sale of enslaved folks in US historical past, got here to be referred to as the Weeping Time.

The document of sale lists greater than 400 males, ladies and youngsters, recognized as chattel and numbered, with their first names, experience and worth.

Tom, 22; cotton hand. Bought for $1,260. Choose Will, 55; rice hand. Bought for $325. Lowden, 54; cotton hand. Hagar, 50; cotton hand. Lowden, 15; cotton, prime boy. Silas, 13, cotton, prime boy. Lettia, 11; cotton, prime woman. Bought for $300 every. Fielding, 21; cotton, prime younger man. Abel, 19; cotton, prime younger man. Bought for $1,295 every.

Beneath the specter of lash whips, ladies wailed for his or her kids, kids for his or her moms, males for his or her wives, wives for his or her husbands – members of the family who would most likely not see one another once more. That they had all been placed on sale to pay the playing money owed of Pierce M Butler, an enslaver who had been married to the well-known British actor Fanny Kemble. Pierce, along with his brother John, had inherited rice and cotton plantations in Georgia from their father, Pierce Butler, one in all America’s “founding fathers” and a signer of the US structure.

In 1859, the youthful Pierce Butler shipped 435 enslaved Africans by steamer and rail from Butler Island and St Simons Island into Savannah. The public sale was extensively marketed. “FOR SALE: LONG COTTON AND RICE NEGROES. A GANG OF 460 NEGROES … Will probably be bought on the second and 3d of March subsequent, at Savannah,” proclaimed the Savannah Republican newspaper on 8 February 1859.

Speculators, traders and slave merchants packed motels, eagerly awaiting the sale on the racecourse, about 3 miles from the guts of downtown Savannah. Mortimer Thomson, a reporter for the New York Tribune, described the therapy of the folks that had been to be auctioned: “Instantly on their arrival, they had been taken to the racecourse, and there quartered within the sheds erected for the lodging of the horses and carriages of gents attending the races. Into these sheds they huddled ‘pell mell’, with none extra consideration to consolation than was essential to forestall their turning into unwell and unsaleable.”

The ladies wore gray turbans. One carried a string of blue and yellow beads. They slept on flooring and ate skinny meals of rice and beans with bits of bacon and corn bread.

On their faces was carved grief. Some stared vacantly. Others rocked in fear. Youngsters clung to their moms’ clothes, as they waited every week whereas preparation for the sale of people was below approach. Potential patrons flocked to the stalls to look at the folks. They slid their palms up and down the our bodies of the boys, ladies and youngsters, searching for bruises. They pushed again their heads and opened their mouths, checking enamel. They pinched pores and skin and walked them up and right down to detect any indicators of weak spot.

Lastly, the enslaved Africans, the ancestors of the Gullah Geechee, had been marched to the “grand stand” for remaining gross sales. When it was all mentioned and performed, Pierce Butler gave every a silver greenback, then he celebrated the sale with champagne.

As we speak, the positioning of this occasion, a area of greater than 12 acres, lies on non-public property on the outskirts of Savannah. In the future final summer season, Patt Gunn, a Gullah Geechee elder, walked me to the place the place her ancestors had been bought 163 years in the past. A guard watches the doorway, stopping any intruders.

“It’s a crying place,” mentioned Gunn, her head shaved like a warrior. “I’ve poured so many libations right here. Yearly, on the two and three March, we do commemorations downtown” – the place the town belatedly put in a historic marker in 2008. “We will’t do commemorations on the land, as a result of that’s non-public property.”

Gunn, the founder and creative director of the Saltwata Gamers, a folks arts group of singers who carry out the standard name and response “ring shout”, mentioned it was the Gullah Geechee folks bought right here in the course of the Weeping Time who picked the Sea Island cotton shipped to England. “These can be individuals who would turn into the growers of the cotton that flowed proper into Manchester and to Bristol, that flowed proper into the Industrial Revolution,” Gunn mentioned. “The cotton, rice, indigo got here out of Savannah and went to England.”

‘No dwelling, no hope, no assist’

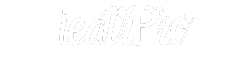

The Gullah Geechee persons are direct descendants of enslaved Africans who picked rice, indigo and the distinctive Sea Island cotton prized by merchants in Manchester. What makes the neighborhood distinctive is its connection to a shared tradition that started to type within the 18th century, when plantation homeowners in low-lying coastal areas determined that rice could possibly be profitably grown there. The planters engaged in a brutal slave commerce. They sought out African individuals who had specific experience in rice cultivation in west Africa, capturing them and forcing them into enslavement to provide rice on their plantations.

Even earlier than “emancipation” on the finish of the US civil warfare, many Gullah Geechee folks lived in relative isolation on the Sea Islands off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina, away from absentee landowners who typically left overseers in command of their plantations, particularly within the malarial wet season. For generations, these enslaved Africans maintained their shared tradition by way of music, language, faith, meals and information of the land and sea.

To assist protect this historic hall, which features a 475-mile stretch of coastal land and islands, the US Congress designated it a nationwide heritage web site in 2006. Greater than 200,000 Gullah Geechee folks, a few of whom converse Gullah, a mixture of English and west African languages, nonetheless stay within the hall alongside the Sea Islands. It’s the place Black folks lengthy sought refuge from “buckra”, a west African phrase for white folks that was initially used within the Sea Islands and the Caribbean to confer with slave masters.

However all alongside this heritage hall, Gullah descendants are nonetheless battling to protect their historical past, language and land in opposition to a wave of gentrification and displacement. In Savannah, Gullah descendants are combating to protect quarantine websites the place English slave ships first arrived from west Africa in 1766 with 78 enslaved Africans. In Hilton Head, South Carolina, a Sea Island that pulls tens of millions of vacationers, the combat is to cease builders constructing luxurious resorts atop Gullah land and cemeteries subsequent to the ocean. On Sapelo Island, off the Georgia coast, which isn’t accessible by automotive – descendants of the enslaved are combating to retain their property.

“Our African cultures are so evident in our way of life and have been intact and handed down generationally,” mentioned Victoria Smalls, the manager director of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Hall. “It’s vital to protect this tradition as a result of it was our ancestors that constructed America, introduced the wealth to America and in lots of instances haven’t been recognised.”

Marquetta L Goodwine, an creator and artist often known as Queen Quet, the chieftess of the Gullah Geechee Nation, instructed me that it was crucial to maintain the traditions alive, not merely to recollect them. “In terms of Gullah Geechee heritage and tradition, which incorporates our language, songs and a myriad of different traditions, I don’t do preservation,” Quet mentioned. “I stay my traditions and combat for them to be precisely represented as a result of it’s a matter of the continuation of the tradition.”

Gullah elders within the hall say there’s a direct connection between its historical past, the crops their enslaved ancestors picked and the wealth they generated for others. What, they ask, will be performed to restore the hurt and trauma so many generations later?

Alongside the Gullah Geechee hall, beneath the Spanish moss that hangs from oak bushes, amid magnolias, the singing of cicadas, relentless mosquitoes, candy seagrass and black waterways that stretch like veins throughout the land, is the story of distant wealth generated by the cotton triangle. The enslaved Africans right here produced tens of millions of kilos of cotton exported from America to England.

Even after Britain declared the slave commerce unlawful in 1807 and abolished enslavement in 1833, it continued to revenue from the establishment of human bondage. Wealth from cotton constructed the monetary business and the textile mills, the place cotton fibre turned twists, spun into thread, and woven into fabric. Fuelling the Industrial Revolution in Lancashire, Cheshire and Manchester was the “white gold”, nice puffs of Sea Island cotton, wanted by merchants for its luxurious extra-long fibres.

In an notorious 1858 speech on the US Senate ground, Senator James Henry Hammond, an antebellum politician and planter, defined the ability the American south wielded because the world’s largest provider of cotton. Hammond, who had been a governor of South Carolina, threatened the north with a portentous warning that the American and English economies would crash with out cotton. It was a merciless speech, which totally dismissed the truth that the lives and freedom of 1000’s of enslaved Africans had been at stake.

“What would occur if no cotton was furnished for 3 years?” Hammond requested on 4 March 1858, three years earlier than the civil warfare erupted. “I cannot cease to depict what everybody can think about, however that is sure: England would topple headlong and carry the entire civilised world together with her, save the south.”

The south was so assured on this useful resource on which industrialised nations depended, that it believed it could win any civil warfare. “You dare not make warfare upon cotton!” shouted Hammond. “No energy on earth dares make warfare upon it. Cotton is king.”

African American abolitionists corresponding to Sarah Parker Remond would combat again, waging a warfare for freedom, travelling throughout the states and crusing throughout the ocean to England, Scotland and Eire to lift consciousness in regards to the brutality of slavery. This refined lady, born right into a household of freedom fighters in New England, held audiences in Europe spellbound. She demanded that England, the place folks lived white lives indifferent from the horrors of slavery, ought to be part of the combat to finish slavery in america.

“For the slave there is no such thing as a dwelling, no hope, no assist,” Remond instructed an viewers in Manchester in 1859, interesting to cotton mill staff to affix the anti-slavery motion. “After I stroll by way of the streets of Manchester and meet load after load of cotton, I consider these 80,000 cotton plantations on which was grown the $125m price of cotton which provide your market, and I do not forget that not one cent of that cash ever reached the palms of the labourers.”

So a few years later, alongside the Gullah Geechee hall, the historical past of cotton nonetheless lingers within the panorama, of winding waterways, by way of golden marshes, alongside sacred islands and previous plantations. However what’s lacking from this panorama is proof that any of the nice wealth generated by the palms that picked the cotton ever fell to their descendants.

“The Gullah Geechee, they had been the consultants. They had been the purveyors of the talents to develop the cotton, rice, indigo and even sugar,” mentioned C Sade Turnipseed, an assistant professor of historical past at Mississippi Valley State College. “They usually understood their energy within the manufacturing.”

Turnipseed is main an effort to lift $26m (£21m) to construct a monument, museum and to determine a “cotton pickers’ path” of historic markers that may hint the legacy of slave cotton. “The path would observe the triangular commerce, from Africa, Barbados, Charleston, south by way of the Cotton Kingdom and again to Europe in the identical approach textiles and cotton travelled,” Turnipseed mentioned. “There ought to be [a historic marker] in each state that grew cotton, and even on Wall Road and in Manchester.”

There may be generational ache linked to a “money crop” that African Individuals picked, throughout and after slavery, with out sharing within the wealth their labour generated. Turnipseed recalled visiting Manchester on a analysis journey: “I went to a museum all in regards to the cotton, ginning and textile. There may be an exhibit there exhibiting a cargo from the [Mississippi] Delta. However we have to join all of it the best way to Africa. It’s about telling the reality.”

Britain might assist on this regard, Turnipseed mentioned, with recognising that historical past of cotton and paying reparations to descendants of cotton pickers who by no means benefited from the wealth. “Similar to the French despatched over the Statue of Liberty,” Turnipseed mentioned, “they will help construct a monument to the cotton pickers.”

‘The ghosts are dying’

Land retention within the hall is the important thing to survival for the Gullah Geechee and their tradition. However Black-owned land is being misplaced below strain from outrageous property tax hikes, predatory land speculators, industrial growth and disputes over what is named “heirs’ property”.

Heirs’ property, land owned “in frequent” by descendants of Gullah Geechee, is a practice of property transference established after Jim Crow, when Black landowners had been typically reluctant to file wills in courts run by white folks. As a substitute, many Gullah willed property by phrase inside the village communities.

A lot Gullah family-owned land was due to this fact bequeathed to kids in offers during which their heirs would turn into joint homeowners of the land. As land within the Gullah hall turned extra helpful, issues arose. Heirs’ property descendants typically don’t have any clear titles to the land. Compounding the sophisticated historical past, helpful land, way back bought by Gullah ancestors after emancipation, is now being bought by Gullah Geechee descendants who by no means lived within the hall, however inherited plots as their elders died.

“Heirs’ property, undoubtedly, is likely one of the drivers of African American land loss,” mentioned Willie Heyward, a lawyer in Charleston, South Carolina whose agency specialises in resolving heirs’ property instances. “The Gullah tradition is invested in land. With out the land, the tradition is misplaced. Candy grass baskets are good, however due to long-term isolation, that tradition shall be disrupted. Fences are going up. No trespassing indicators are going up. Subdivisions are going up with gated communities and so forth.”

“As soon as land is gone,” Heyward mentioned, “that shall be a wrap.”

As growth consumes the hall, the destruction of Gullah cemeteries has additionally turn into widespread. “The Sea Islands weren’t ‘the Sea Islands’ they’re now,” mentioned Althea Natalga Sumpter, a Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Hall commissioner. “They weren’t resort areas. They had been areas that used to have cemeteries and they’re now resorts. There are actually homes and resorts on prime of cemeteries.”

“There are such a lot of outsiders who’re fascinated: ‘We will stay by the seaside,’” Sumpter mentioned. “I’m like, ‘Oh, please, you don’t stay on the seaside. You go to the seaside.’ It’s a fixed battle to retain land.”

Most of the grave markers that will have seemed like nothing to the outsiders have vanished. “Within the Nineteen Forties and Nineteen Fifties, there have been African headstones and sculptures close to Charleston they usually had been simply taken,” mentioned Sumpter, a scholar and ethnographer. “These headstones had been unimaginable wood sculptures.” Sumpter, who researched and recorded tales of Gullah Geechee elders, says it’s crucial to gather the tales and save the tradition “earlier than the ghosts die”.

“The ghosts are dying. That’s the approach my grandmother would describe the hyperlink with those that have come earlier than,” Sumpter mentioned. “Linking with the previous is what I felt I used to be doing when an elder cousin requested for me to take a seat together with her to listen to extra tales, after which she instructed me about her grandfather who ‘came to visit within the boat’. I used to be holding the palms of a cousin who discovered about life from an enslaved African. She died a number of weeks later, the hyperlink to that ghost damaged.”

Emory Shaw Campbell, a tall man with carved options, was born and raised on Hilton Head Island. Campbell can keep in mind what Hilton Head was like earlier than the bridge was constructed, earlier than the million-dollar mansions, golf golf equipment and personal resorts.

Campbell, whom some name the “Godfather of Gullah”, an ideal elder who led work on translating the Bible into the Gullah language, remembers the elders who spoke pure Gullah. “I’m 80 years previous,” he mentioned, “so I can keep in mind again to the Nineteen Forties on this island. They spoke African and English phrases combined. We’d giggle at them. We didn’t even know they had been talking their language from Africa.”

Campbell mentioned he wished he had had the wherewithal to take down their tales. “My grandmother might have instructed me about her mom’s enslavement,” Campbell recalled. “I didn’t ask sufficient questions. I didn’t know sufficient to ask.”

Campbell remembers Hilton Head as an exquisite refuge, disconnected from the mainland. It was uncommon to see a white individual. On Hilton Head, Gullah households lived on household land, hunted, fished and took boats throughout the black waterways. Then, in 1956, the federal government constructed a bridge and life modified.

“Now that the islands are bridged and mosquito management has taken place, the islands have turn into a playground for rich folks,” Campbell mentioned. “And our historical past is being misplaced in all of that exercise of golf and tennis. You wouldn’t know this was a spot the place enslaved folks settled after the civil warfare.”

Hilton Head, he mentioned, had turn into a premier resort location. “So one involves Hilton Head and doesn’t count on to see any households of previously enslaved folks,” Campbell mentioned. “However we’re hanging on.”

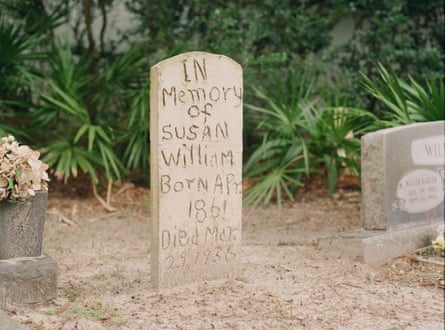

To get to his household’s cemetery, Campbell should now go by way of a guarded entrance to a non-public resort. One afternoon final September, I drove with him to go to the cemetery. On the gate, Campbell instructed the guard he was visiting his household’s graves. “Oh, certain,” the guard mentioned, and handed him a customer’s go. We drove previous multimillion-dollar homes, clubhouses, tennis courts, swimming swimming pools, earlier than arriving at a tiny plot, surrounded by a fence, and bounded on all sides by luxurious houses.

“That is the cemetery,” Campbell mentioned, trying to find the grave of his nice grandmother, Susan Williams, who was born in 1861. A condominium constructing, with huge home windows and balconies, has been constructed so shut it abuts the cemetery. The luxurious constructing now stands between the graveyard and the water, blocking the view from the cemetery to the river.

“The custom was to bury the our bodies dealing with east,” Campbell mentioned, “but additionally in case you had been close to water, that the cemetery or graves can be close to the river or close to the waterway. The custom is that the spirit can be free to maneuver again to Africa.”

These first few generations of enslaved Africans saved their traditions alive as they longed to return to the continent. “They yearned to return dwelling and that was Africa,” Campbell mentioned. “Individuals by no means relinquished that want to return dwelling. That’s the reason you continue to see the basket weaving, the fishnet weaving, it has been instilled in households, even all through the brutality of slavery, that remained the hope of going again to Africa.”

Campbell seemed up on the condominium constructing, so near the cemetery that one can attain over the fence and contact it. “We had been incensed when this constructing obtained right here,” Campbell mentioned, “as a result of we didn’t know folks can be constructing this near a graveyard. Our custom in our tradition is all the time exhibiting respect for a cemetery. You simply didn’t do something close to a cemetery. This tradition reveals us, and has proven us, a cemetery is simply one other place. Nothing sacred about it.”

‘Gullah persons are not fence folks’

Just a few days later, I met Maurice Bailey on the ferry dock on Sapelo Island, which the Gullah Geechee take into account a sacred place, reachable solely by boat. We drove in his van below a thick cover of bushes that draped one-lane roads, previous previous relics of homes made with sea shells, previous previous plantation mansions.

The van crept alongside the highway as if it had been going again in time. As soon as there have been greater than 400 enslaved Africans residing right here, who largely grew cotton, rice, indigo and sugar cane. The island had been remoted for greater than 200 years, so the tradition survived lengthy after slavery ended. “They didn’t have a daily ferry system leaving Sapelo till 1978,” Bailey mentioned.

As we drove previous former plantation homes, he defined how growth had modified the island. A lot of Sapelo Island was purchased in 1969 by the state of Georgia, and lots of the Gullah households had been moved to a neighborhood on the tip of the island referred to as Hog Hammock. From a inhabitants of greater than 800 Gullah Geechee individuals who lived right here, there are actually about 30 Gullah folks remaining.

The remainder of the island is populated by “newcomers”, whom the Gullah name buckra.

“They used a whole lot of intimidation,” mentioned Bailey. “We had been within the ‘good ol’ south’. We had been remoted on Sapelo. Again then, we didn’t have a approach to get off Sapelo, besides by bateau boats. My grandfather would get into his bateau and row off.”

Bailey mentioned lots of the buckra used worry techniques and tips to deceive the Gullah Geechee elders to maneuver from their land. “I do know from my grandmother’s time, they’d speak about Richard Reynolds,” the tobacco firm tycoon, who purchased a lot of the land on the island within the Nineteen Thirties. “He would promise folks electrical energy in the event that they moved. He would promise folks constructing supplies in the event that they moved. I do know my grandfather was one in all them. He was instructed he wouldn’t should pay for it. When he moved to construct his home, they circled and charged him.”

“If you will get the elders to maneuver, different folks would observe,” Bailey mentioned. “There was intimidation about jobs. They had been in command of the ferry system. So that you had been threatened in regards to the ferry and in regards to the job. How are you going to feed your loved ones? We misplaced land. Individuals grew up with the mentality, ‘Don’t mess with buckra. You possibly can’t win.’ Even the previous folks on this neighborhood nonetheless imagine that.”

In 2012, many individuals on the island had been hit with a property tax rise of greater than 500%. “Now, we’re coping with gentrification, the identical factor,” Bailey mentioned. “White folks realise how helpful our land is. Now we’re combating exhausting to maintain it.”

About 60 miles (100km) up the coast On St Helena Island, simply north of Hilton Head, Gullah Geechee homes sit tucked away on ancestral land. Down winding roads, previous these Gullah villages and previous cotton plantations, there are extra indicators buckra has arrived. Large fashionable homes have been constructed subsequent to conventional Gullah communities. The newcomers, rushing by in golf carts, appear to not care in regards to the historical past right here, the disappearing connection to the lives of enslaved Africans and the tradition they introduced with them. Nor do they appear to acknowledge the grounds upon which they’re constructing are sacred to the Gullah Geechee.

Donellia Chives, who was born within the Sea Islands, drove me down a dust highway, “the Avenue of Oaks”, which results in the Coffin Level plantation, the place enslaved Africans as soon as grew Sea Island cotton.

A white man, sporting a white hat, whizzed by in a white golf cart. “When communities actually begin to change, you see the golf carts a complete lot extra,” mentioned Chives. “We joke on a regular basis. There are white picket fences and golf carts. That’s their lifestyle. Generally, they arrive in and construct a fence first to let you realize that is ‘my area and my territory’. Gullah persons are not fence folks. We strive to not have boundaries when doable.”

“Individuals have stolen land or taken it for very low cost from Gullah Geechee folks to develop resorts and homes,” mentioned Chives. In some instances, the Gullah had been cheated out of land, she added. “They bought it for little or nothing. There are tons of the way folks had been deliberately manipulated out of their property.”

We drove by way of St Helena to the grounds of Penn Middle, previously often known as Penn College, which was based in 1862 to offer training to kids of lately freed enslaved Africans. The campus appears frozen in that historical past.

Through the civil rights motion, the college was a refuge for voting rights staff. It was one of many few locations within the south the place Black folks might meet with white sympathisers to organise. The Klan, it’s mentioned, knew to not cross the bridge and confront Gullah folks, who protected the campus. Martin Luther King Jr typically got here right here to retreat. It’s a tranquil area stuffed with energy: whereas staying within the Hastings Gantt cottage at Penn Middle, King wrote his “I’ve a dream” speech.

Chives, her head wrapped in a crimson scarf, walked to the sting of a marsh on the campus. “We’re standing on sacred grounds,” she mentioned.

A trustee of Penn Middle, she nonetheless marvels on the land and the legacy of the enslaved Africans who had been introduced right here, chosen intentionally for his or her information of rice and cotton cultivation. Regardless of the oppression of slavery, they held on to African traditions, language and music.

“The Gullah Geechee persons are residing historical past,” Chives mentioned. “That is proof of our ancestors’ hand on the land. That is divinely protected, I do know that. It’s as much as us to do what we will to protect this historical past and this land.”

The Spanish moss sways. Generally, the whispering bushes cease Chives in her tracks.

“After we really feel the breeze coming off the bushes, the ancestors are letting us know they’re right here,” Chives mentioned. “I stay quiet, so I can hear. The ancestors wish to be acknowledged. They wish to see and listen to that we care – to know their work was not in useless.”

The land and its recollections

On Tybee Island, a tiny Sea Island close to Savannah, Patt Gunn, the Gullah Geechee elder who works tirelessly to maintain her folks’s historical past alive, introduced me to a different unmarked web site, close to a waterway the place slave ships as soon as docked at quarantine stations earlier than touchdown.

The sick and the “harmful” enslaved Africans susceptible to mutiny had been thrown overboard right here at these lazaretta websites. The phrase lazaretta, or lazaretto, comes from Italian and was utilized in Europe to confer with isolation homes for these with leprosy or the plague. Previous maps of the world cite 27 lazaretta stops, however these stations of the slave commerce should not recognized right this moment with historic markers.

At this cease, somebody had posted “hold out” indicators. “Even the sacred locations the place we wish to wail, we will’t even go there,” Gunn defined. Just a few months earlier, Gunn, with the Saltwata Gamers, the activist Rozz Rouse, and the human rights activist Julia Pearce, had held a commemoration on this lazaretta web site.

“Coming right here and seeing gates is like being in bondage,” Gunn mentioned. “We will’t stroll on the land. We will’t wail on the land or sit in wonderment and picture the ships that got here in from west Africa with our folks in bondage.”

We drove to the guts of downtown Savannah, the place Gunn leads excursions on the historical past of enslavement. She explains the paths that enslaved Africans took as they climbed down from slave ships and had been marched over streets paved with ship ballast stones. The enslaved Africans had been brazenly traded close to Ellis Sq., bought in Wright Sq. and detained in Johnson Sq..

As we retraced the steps that enslaved Africans took, we stopped at a limestone cavern close to the Savannah River. Inside, Gunn sang to the ancestors, imagining their worry, starvation and thirst in bondage. “Carry me a little bit water, Molly,” Gunn chanted. “Carry me a little bit water, little one. Molly got here a operating, bucket in her hand. I would like a little bit water each occasionally.”

She needs folks to recollect what occurred to the enslaved Africans who would turn into the Gullah folks – the individuals who picked rice, indigo and the cotton heading for England. “From the caverns, you may see the insurance coverage places of work, cotton factories, the delivery consultants, all invoice of lading places of work for customized brokers,” Gunn mentioned, trying from the cavern as much as centuries-old crimson brick buildings with curved wrought-iron balconies.

One can think about the bustling market, the requires gross sales, the enslaved Africans strolling from ships over these paved streets. “The whole lot downtown needed to do with enslavement,” Gunn mentioned. “The bankers, the brokers, they had been all down right here.”

Gunn needs to protect the historical past of the Gullah individuals who picked the cotton that produced the wealth in Manchester. Although separated by an ocean, the tales of the enslaved Africans bought on the Weeping Time and the story of cotton and the wealth it produced are linked by a historic thread.

Afterward, 3 miles from downtown, Gunn, sporting coral pink together with her head wrapped in a teal silk, stood exterior the gate blocking entry to the Weeping Time web site. As if on cue, an acknowledgement of the historical past of the sale carried out below a torrential downpour, it began to rain.

“That’s sacred land,” Gunn mentioned. “It breaks my coronary heart as a result of all of that ought to be a part of commemorative land. There ought to be bricks with the names of the 429 that had been bought within the Weeping Time. It is sort of a sacrilege. I wish to chant a music and name out to them, my ancestors, ‘I do know you got here this manner.’ It’s like my soul is weeping.”

In regards to the creator

DeNeen L. Brown is an award-winning author and an affiliate professor on the Philip Merrill School of Journalism

The Guardian’s founders and transatlantic slavery: what ought to it imply? Be a part of the Guardian’s editor-in-chief, Katharine Viner, the historian David Olusoga, the lead researcher Dr Cassandra Gooptar, and the Cotton Capital editor Maya Wolfe-Robinson for a particular occasion as they focus on the Guardian’s two-year investigation into its founders’ hyperlinks to the cotton commerce and enslaved folks. Chaired by the Guardian journalist Joseph Harker. Register right here to affix on Thursday 30 March, 7pm BST (2pm EDT)

Trending

-

Bank and Cryptocurrency12 months ago

Cheap Car Insurance Rates Guide to Understanding Your Options, Laws, and Discounts

-

Bank and Cryptocurrency12 months ago

Why Do We Need an Insurance for Our Vehicle?

-

entertainement6 months ago

entertainement6 months agoHOUSE OF FUN DAILY GIFTS

-

WORD NEWS1 year ago

Swan wrangling and ‘steamy trysts’: the weird lives and jobs of the king’s entourage | Monarchy