WORD NEWS

Champion of the gorillas: the vet preventing to avoid wasting Uganda’s nice apes | Conservation

The Bwindi Impenetrable Forest is tucked away in a distant nook of southwest Uganda. That means “place of darkness” within the Runyakitara language, this dense, mist-swathed rainforest makes for a very good hiding place for half of the world’s remaining mountain gorillas. The opposite half, which the American primatologist Dian Fossey so famously befriended, stay in Rwanda’s Virunga nationwide park.

These majestic however shy creatures – whose existence now generates about 60% of Uganda’s tourism income – like to cover, particularly once they know veterinary intervention is afoot. The gorillas are all the time outsmarting the people – in the event that they see somebody carrying a dart gun (for sedation, vaccinations, drugs, and many others), they’ll stroll backwards in order to not expose their backs, the place the dart must land. In addition they wish to mock-charge at people, stopping abruptly to point they imply no hurt, but leaving little doubt as to who holds the ability. And in the event that they’re actually not feeling the presence of people, they’ll outright cost at you.

“If the silverback prices, nobody will have the ability to go to that group,” says the award-winning Ugandan wildlife vet and conservationist Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, through Zoom from her dwelling in Entebbe, which she shares along with her husband, Lawrence, and sons, Ndhego, 18, and Tendo, 14. “To ensure that him to simply accept people, it’s important to keep very calm, hold your voice down and keep away from eye contact. That’s the way it needs to be with wildlife – they need to be in cost.”

We’re right here to debate the 53-year-old’s forthcoming memoir, Strolling with Gorillas: The Journey of an African Wildlife Vet, a humbling account of a life devoted to the survival of Bwindi’s endangered gorillas and their human neighbours. You might not have heard of Kalema-Zikusoka, however the ebook’s foreword by Dr Jane Goodall provides some indication of her standing within the conservation world. “It’s hardly shocking that this outstanding girl has been the recipient of numerous awards and prizes,” writes Goodall (in 2021 she was named the UN Surroundings Programme’s Champion of the Earth, and final 12 months gained the Edinburgh Medal for her contribution to science). “She has made an enormous distinction to conservation in Uganda.”

That distinction has largely been achieved by way of light tenacity and spectacular networking expertise, even since her scholar days – Kalema-Zikusoka launched herself to Goodall as an undergraduate on the Royal Veterinary Faculty in London after attending certainly one of her talks. And when she realised her dream job didn’t exist (whereas nonetheless at RVC), she wrote to the one who may have the ability to create it – the top of Uganda nationwide parks – to say she needed to grow to be its vet.

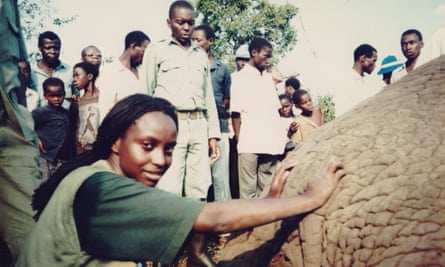

And so in 1996, aged 26, Kalema-Zikusoka grew to become Uganda’s first ever wildlife vet. At this level, there have been solely about 300 Bwindi gorillas left within the forest. After almost three many years of tending to them, she now estimates a complete of about 500 – the final census in 2018 counted 459, sufficient to downgrade the mountain gorilla from critically endangered to endangered.

It’s an achievement that has prompted invites to take a seat on quite a few worldwide conservation boards, together with the Dian Fossey-founded Gorilla Organisation, for which she volunteered whereas at RVC, “stuffing envelopes late into the evening,” says its government director Jillian Miller. Because the late Nineties, Kalema-Zikusoka has been a trailblazer of “neighborhood conservation”, notes Miller, at a time when most conservationists took “a top-down, colonial” strategy. “Gladys was a pure at getting the help of native individuals.”

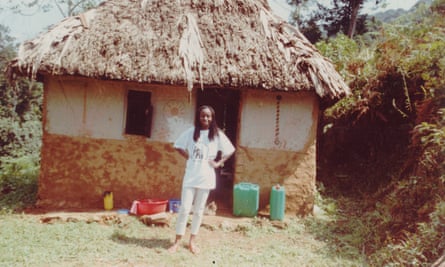

Born in Kampala, Uganda, in 1970, because the youngest of six siblings, Kalema-Zikusoka grew up towards the backdrop of Idi Amin’s army dictatorship. Aged two, her father, William Wilberforce Kalema, a former cupboard minister below President Obote, was kidnapped and murdered by Amin’s troopers. For her security, Kalema-Zikusoka was despatched to boarding college from the age of seven, variously in Uganda, Kenya and the UK, and within the Eighties her mom, Rhoda Kalema, now 93, grew to become certainly one of Uganda’s first feminine members of parliament, for the Uganda Patriotic Motion.

That was not with out hazard both – she was arrested 3 times and as soon as jailed for her politics. The legacy of each mother and father “enduring many hardships” is, writes Kalema-Zikusoka in Strolling with Gorillas, what impressed her to “dig deep to seek out my braveness”.

As a baby, although, animals had been her escape from the “cloud of terror”, and he or she’d retreat to the strays turned pets that her older siblings introduced dwelling. Bby the age of 12, her coronary heart was set on changing into a vet – not a revered vocation in Uganda, she explains in her memoir: “Folks don’t place a lot worth on pets in a creating nation with a lot human struggling.” After a college safari journey, the place she noticed how Amin’s rule had decimated Uganda’s animal populations, she knew wildlife veterinary apply was her calling.

Her first encounter with a wild gorilla, at 24, was “a life-changing expertise” – and never only for that heart-pounding second of “deep reference to certainly one of our closest cousins,” as she writes. She had volunteered for a Ugandan research whereas at RVC, accumulating Bwindi gorilla faeces and found that gorillas visited by vacationers carried a higher parasitic burden. “What struck me,” she remembers, talking from the sparsely adorned research through which she wrote her memoir, “was how related we had been to one another and but we’re placing their lives in danger. We needed to do one thing about it.” That lightbulb second has guided her work ever since. “If you enhance the well being of people, you enhance the well being of the animals,” she explains. This holistic strategy to conservation, of which Kalema-Zikusoka was an early advocate, is now referred to as One Well being.

It’s why you gained’t discover any cosy photographs of Kalema-Zikusoka cuddling wild gorillas, like Fossey and Attenborough. Except veterinary therapy is required, she and her group of rangers, porters and trackers preserve a distance of 10 metres from the gorillas. Sharing 98.4% of our DNA with them means we will simply make one another sick with zoonotic ailments – these transmitted between animals and folks, resembling Covid, TB and scabies. Even again in 2011, she was encouraging vacationers to put on masks on gorilla treks, and throughout the pandemic went to nice lengths – together with lobbying the Ugandan authorities for precedence testing for Bwindi individuals – to make sure not one of the mountain gorillas caught the virus (they didn’t).

One other zoonotic pandemic is “inevitable, sadly,” says Kalema-Zikusoka, whose experience led to her appointment on the WHO’s Particular Advisory Group for the Origin of Novel Pathogens (based in 2021 to find out the supply of Covid and stop the subsequent pandemic). It’s inevitable, she explains, “as a result of we’re disrupting wild animals’ habitats a lot.” As noticed with the Bwindi gorillas, “while you destroy habitats, these animals will go into individuals’s gardens”. Mountain gorillas, by the best way, discover yard banana crops irresistible, and the following proximity to people allows “ailments to leap forwards and backwards” between species. Whereas the subsequent zoonotic pandemic could possibly be attributable to avian influenza, she thinks it would “most likely be [caused by] one other coronavirus. It’s the worst sort of virus. As a respiratory sickness, it’s extremely contagious, however the majority of individuals don’t die, so it simply retains going and going. And it’s in a position to mutate.”

Given the nice apes’ sensitivity to human illness, is gorilla tourism actually of their finest pursuits? It’s sophisticated. Kalema-Zikusoka sees tourism as a mandatory evil. It’s true, she writes, that habituated gorillas – these accustomed to people – are extra susceptible to illness and poaching and but, “The mountain gorilla, the place there’s a thriving tourism business, is the one gorilla subspecies whose inhabitants is rising.”

What about the local people’s finest pursuits? There are about 100,000 individuals dwelling in parishes bordering the nationwide park. Properly, it might go both manner – and has, over time. After the Bwindi mountain gorilla was found in 1987, the early days of Uganda’s gorilla tourism triggered a messy vicious cycle. Because the gorillas misplaced their worry of people, “They’d go into individuals’s gardens and catch human ailments,” says Kalema-Zikusoka. In the meantime, pushed by poverty, villagers would head into the forest to cut down wooden and lay snares for bush pigs and duiker (a sort of antelope), which led to lack of habitat, gorillas being snared and folks getting sick from diseased bushmeat. Plus, the locals grew resentful of gorilla tourism, understanding how a lot westerners had been paying and that none of it benefited them.

By means of Kalema-Zikusoka’s many bridge-building interventions, that vicious cycle has been reworked right into a virtuous one, with a number of programmes being expanded to different elements of Uganda and past. In 2003, she based Conservation By means of Public Well being (CTPH), an NGO by way of which she might fundraise and nonetheless run One Well being programmes in Bwindi. She recruited her husband, a Ugandan telecoms entrepreneur whom she’d met whereas finding out for her masters at North Carolina State College, as treasurer, and her former analysis assistant, Stephen Rubanga, as secretary; CTPH now has 35 staff.

As a substitute of parachuting in outsiders, native volunteering has been key to its success. This empowers the Bwindi individuals and encourages them to be stewards of their very own surroundings. To maintain the gorillas away from these bananas, Kalema-Zikusoka shaped the Gorilla Guardians – native volunteers to herd gorillas again to the nationwide park. Twenty years on, Bwindi’s 119 gorilla guardians are “a supply of satisfaction to the neighborhood,” she says. She additionally launched household planning to Bwindi, in a manner that was sympathetic to the neighborhood. What went down finest, she discovered, was contraceptive injections each three months (extra handy; much less explaining to do to sceptical husbands), administered by skilled volunteers from the villages. And she or he established volunteer well being guests from every village who’d train households about hygiene and sanitation. Now, “when gorillas forage of their gardens,” she writes, “they discover cleaner houses with no soiled clothes on scarecrows, no open defecation and no uncovered garbage heaps.” With the gorillas falling sick much less typically, tourism has prospered.

And now that the locals get a share of the vacationer greenback – by way of promoting meals, crafts and lodging, or as porters, guides and rangers – they see an incentive to guard the gorillas (many rangers are former poachers and luxuriate in higher pay and extra common work). Just a few years in the past, a really aged silverback was discovered eating on villagers’ bananas and berries, however the locals let him graze. When he died a couple of days later, aged round 50, about 100 members of the neighborhood attended his funeral. “This act of kindness signified how far conservation efforts have are available in Bwindi and that true friendship between individuals and wild animals is, certainly, potential,” says Kalema-Zikusoka.

But it’s a fragile ecosystem. When Covid hit and tourism halted, poaching and poverty returned. It could not shock you to listen to that Kalema-Zikusoka created an answer, offering 1,000 of Bwindi’s most susceptible households with seedlings of fast-growing meals crops – pumpkins, maize, floor nuts, beans, onions, tomatoes, amaranthus, spinach, kale and cabbages.

Neighborhood conservation is an costly enterprise, although. The proceeds of the memoir will go straight again to CTPH, she says, including along with her prepared giggle, “ what it’s like when you’ve your individual organisation – you find yourself giving all the things to it.”

In 2015, Kalema-Zikusoka based Gorilla Conservation Espresso as one other option to maintain her work. Though it hasn’t but damaged even, this social enterprise now helps 500 pretty paid, well-trained espresso farmers, 120 of whom are feminine. The premium Arabica roasted espresso will be purchased in Britain (by way of moneyrowbeans.com), the US, Canada and New Zealand.

The necessity for funding is relentless, and anybody who’s ever tried to fundraise will know the way tough that’s. But in 20 years, Kalema-Zikusoka estimates that they’ve raised greater than $6.5m. How? “Gladys is all the time cultivating allies and donors wherever she goes,” says Miller. Pushed extra by function than ego, it appears, she sees herself much less as a pacesetter and extra “somebody with an urge to get issues carried out”.

It’s all of the extra outstanding given the hangover of colonialism in African conservation, plus the truth that Kalema-Zikusoka continues to be a hands-on vet 15% of the time. When she based CTPH, she was informed by African colleagues, “You’re Black, so that you gained’t have the ability to increase the cash.” Though issues are altering, conservation NGOs are nonetheless “primarily run by white individuals,” she says, “and it’s simpler for these NGOs to boost cash. The funding comes from America, UK, Europe and it’s simpler, I feel, for individuals to present cash to others from their very own nation.”

The purpose is, notes Sir Edward Whitley, a monetary adviser and founding father of the Whitley Awards, which champion such grassroots conservation organisations, that “entrepreneurial conservationists, like Gladys, are expert at discovering inventive options to issues that we, on the skin, might not even know exist”. Kalema-Zikusoka gained the Whitley Gold Award in 2009 (“the inexperienced Oscars,” as she calls it) for excellent management in nature conservation and has since obtained £140,000 in funding from the Whitley Fund for Nature.

Does Kalema-Zikusoka have any enemies? She laughs heartily. “I most likely do. Everytime you’re disrupting the established order, you’re prone to. Some individuals hate vets – old-school conservation has all the time been: ‘Don’t contact the animals, don’t intervene with nature’.” She has, in her time, encountered “chauvinistic, racist bullies”. “You continue to discover such individuals in governments, in donor companies.” She has realized to not take it personally. “I don’t want them to love me,” she says, “however you continue to must win them over – allow them to see you’re working with them, not pushing issues upon them; make them really feel like their standpoint is essential – if you happen to’re going to have a big effect.”

Strolling With Gorillas: The Journey of an African Wildlife Vet by Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikosoka is out 27 April (Arcade Publishing, £20), or at guardianbookshop.com for £17.60

Trending

-

Bank and Cryptocurrency11 months ago

Cheap Car Insurance Rates Guide to Understanding Your Options, Laws, and Discounts

-

Bank and Cryptocurrency11 months ago

Why Do We Need an Insurance for Our Vehicle?

-

entertainement5 months ago

entertainement5 months agoHOUSE OF FUN DAILY GIFTS

-

WORD NEWS12 months ago

Swan wrangling and ‘steamy trysts’: the weird lives and jobs of the king’s entourage | Monarchy