WORD NEWS

The place did the Metropolitan Museum of Artwork get its Native American objects? | New York

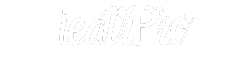

Stepping into the Metropolitan Museum of Artwork, Shyanne Beatty was desirous to view the Native American works that the artwork collectors Charles and Valerie Diker had been accumulating for almost half a century. However as she entered the museum’s American wing that day in 2018, her pleasure turned to shock as two picket masks got here into view.

Beatty, an Alaska Native, had labored on a radio documentary in regards to the two Alutiiq objects and the way they and others like them had been plundered from tribal land about 150 years in the past. Now, the masks had been on show within the greatest and most esteemed artwork museum within the western hemisphere. “It was tremendous stunning to me,” she stated.

The Met’s possession historical past for the masks, often known as provenance, omits greater than a century of their whereabouts. Historians say the masks had been taken in 1871. However the museum’s timeline doesn’t begin till 2003, when the Dikers purchased them from a collector. Possession was transferred to the Met in 2017.

The Dikers, who’ve amassed one of the crucial vital non-public collections of Native American works, have been donating or lending objects to the Met since 1993. In 2017, as different establishments grappled with returning colonial-era spoils, the Met introduced the Dikers’ present of one other 91 Native American works.

A ProPublica evaluation of information the museum has posted on-line discovered that solely 15% of the 139 works donated or loaned by the Dikers through the years have stable or full possession histories, with some missing any provenance in any respect. Most both haven’t any histories listed, go away gaps in possession starting from 200 to 2,000 years or determine earlier homeowners in such obscure phrases as an “English gentleman” and “a household in Scotland”.

Specialists say a scarcity of documented histories is a pink flag that objects might have been stolen or could also be faux.

“That’s a variety of lacking documentation, which is an issue,” stated Kelley Hays-Gilpin, a curator on the Museum of Northern Arizona. The Arizona museum has documented about 80% of its assortment, as has the Brooklyn Museum and different establishments which are thought of much less prestigious than the Met however which have substantial Native American collections. Some museums, corresponding to one on the College of Denver, decline presents which have poor provenance.

For hundreds of years, Native Individuals have decried the looting of the graves of their ancestors by pothunters and scientists and the show of their stays and belongings in museums. In 1990, Congress handed the Native American Graves Safety and Repatriation Act (Nagpra) to facilitate the return of such objects and human stays to the suitable tribes, which the regulation declares are their rightful homeowners.

Nagpra requires federally funded museums to notify a tribe inside six months of receiving their holdings by contacting and consulting with that tribe’s chosen consultant, usually often called a tribal historic preservation officer, and giving them a possibility to reclaim their objects. The regulation additionally mandates that museums file a duplicate of these notices with the Nationwide Park Service (NPS).

These interactions present a possibility for establishments to study extra in regards to the historical past of objects, whether or not they’re genuine or may need been stolen and if it’s acceptable to show them. However as ProPublica has reported this 12 months, museums have usually delayed such discussions whereas maintaining human stays and objects that the regulation says must be returned.

Some items within the Diker assortment are sacred, corresponding to a shaman’s rattle made from human or horse hair; some are funereal and had been buried with the useless. (The Met just lately returned the rattle to the Dikers, and there are “ongoing consultations” associated to another objects, based on the museum.)

“Most of this stuff might solely have ended up in non-public fingers by trafficking and looting,” stated Shannon O’Loughlin, director of the Affiliation on American Indian Affairs, which advocates for tribal sovereignty and the safety of Native American cultures.

“The best way that so lots of these items wound up in museums is horrible,” stated Rosita Worl, president of Sealaska Heritage and a Tlingit citizen. New York regulation goes by the precept of as soon as stolen, all the time stolen, and he or she stated the items had been tainted. “The rightful factor is for these items to be returned residence.”

Initially, lots of the objects had been loans; attributable to a loophole in Nagpra, this meant the museum didn’t must report them to tribes or to the NPS. Up to now, the museum has accepted the switch of 77 of the promised presents from the Diker assortment, based on the Met.

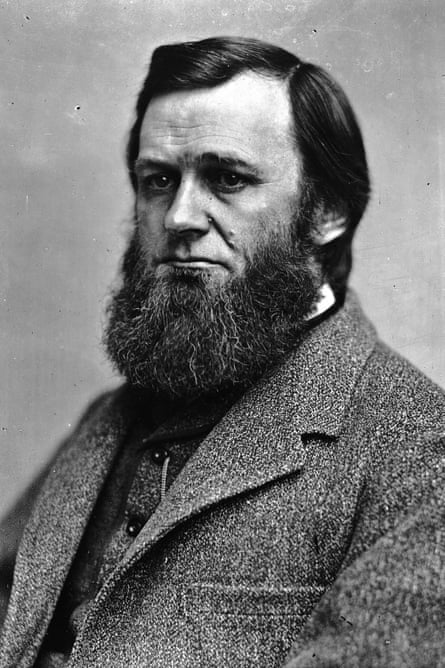

The Dikers have lengthy been identified for his or her artwork assortment and philanthropy.

Valerie Diker is the daughter of the late Norman Tishman, who within the mid-Twentieth century performed key roles in rebuilding Manhattan’s Park Avenue and creating Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. Charles Diker grew up in Brooklyn and have become chairman of Cantel Medical, which offered in 2021 for $4.6bn.

The 2 are founding members of the Nationwide Museum of the American Indian, and Charles is an honorary trustee on the Met. Their accumulating, nonetheless, has been controversial.

ProPublica discovered that the couple had obtained an merchandise from the excavation of an historical Mayan court docket residence in Guatemala. The positioning, La Corona, has been a supply for black market antiquities because the Seventies, based on revealed studies.

In 1995, the Dikers donated a lintel that commemorated the beginning of a Mayan ruler’s son in 660 AD to the Israel Museum. Guatemala didn’t ban exporting its cultural heritage till 1999. However the 1970 Unesco Conference, which the US signed, bans the export and import of cultural property.

“Whereas it might have been authorized to export it on the time, it was actually unethical and it must be returned to Guatemala,” stated Jaime Awe of Northern Arizona College, a Belizean archaeologist who has performed authorized excavations of Mayan websites.

In a press release, the Dikers stated: “We’re nice believers within the Unesco conference.”

Throughout the Nineties, the Dikers additionally donated to the Met three Mayan items from Guatemala, courting from the first century BC to the ninth century AD. Their possession histories are clean or start within the Seventies, throughout Guatemala’s civil battle.

“Our accumulating follow for over 50 years has all the time centered on continuing rigorously, assessing all out there data referring to provenance earlier than buying a piece, and welcoming new data ought to it come to mild,” the Dikers stated within the assertion.

In 2017, when the Dikers promised to offer a few of their Native American assortment to the Met, they insisted that the museum not place it within the corridor of ethnography, however within the American wing alongside Frederic Remington and different American artists.

Some artwork critics applauded that transfer. However many of the 20 tribal historic preservation officers and different tribal representatives that ProPublica interviewed in regards to the exhibit objected to their ancestral objects being handled as ornamental.

Of their assertion, the Dikers stated: “As we stated after we first promised the works to the Museum, our imaginative and prescient and advocacy has all the time been to encourage vast recognition of the ability and sweetness of those works and, by the Met’s stewardship, advance scholarship and understanding of Native American artwork and tradition.”

However ProPublica discovered that after assuming possession, the Met for years didn’t seek the advice of the mandatory tribal officers in a well timed and constant method about objects in its collections. A 12 months handed earlier than the museum contacted somebody on the Alutiiq tribe to tell them that it had their masks. (The Met declined to call the individual it contacted.) 4 years later, the NPS posted summaries that the Met had despatched in September 2022 to 63 tribes related to things within the Diker Assortment. The Met did so after ProPublica requested the museum in regards to the masks and different sacred and culturally delicate objects.

All of the whereas, the museum displayed some objects with incorrect descriptions and omitted or minimized the wars, occupations, massacres and exploitation that dominated the tribes’ previous.

The Met’s descriptions in its shows “are within the land of make-believe”, stated Wendy Teeter, the previous curator on the Fowler Museum on the College of California, Los Angeles. “The general public received’t have a clue as to what a bit actually is or the way it bought there.” This, Teeter stated, “perpetuates stereotypes and bias towards Native individuals”.

Dan Monroe, who helped draft NAGPRA and is a former director of the Affiliation of Artwork Museum Administrators, stated the lengthy delays in notifying tribal representatives and the NPS had been a violation of the regulation: “They’ve a duty to comply with the regulation and are topic to fines in the event that they don’t.”

In a written assertion, the museum stated: “Though some progress has been made in updating the web catalog data and offering extra full provenance data, we acknowledge there may be nonetheless a lot work to do and that that is an ongoing course of that requires relationship constructing, endurance, and nice care. That is necessary work, and it’s exactly one of many intentions of the Dikers to have a big, well-resourced establishment such because the Met dedicate the time and scholarship to those Native objects.”

The museum additionally acknowledged that it was deceptive to make use of “full possession histories as a typical for judging a set”, noting that a lot of the Diker assortment had beforehand been exhibited and researched by different main US museums. “When new details about assortment objects involves mild, we brazenly share it (if suggested by Indigenous leaders to take action), or take away culturally delicate objects from view as requested.”

Throughout its investigation, ProPublica requested the Met to touch upon statements in regards to the assortment. Some sources who had made on-the-record statements that had been shared with the museum by ProPublica later requested to withdraw their statements. One indicated that they’d been contacted by a Met worker. (The Met stated it continually engaged with a variety of execs and didn’t exert any stress on sources for this story.)

The Dikers declined interview requests. In a written assertion to ProPublica, they stated: “For almost 50 years, inspiring appreciation for the humanities of Native America has been our best ardour.” The couple additionally stated that that they had assessed “all out there data referring to provenance” earlier than buying the works.

If a museum can show it has authorized title, that means that the thing’s creator, their descendants or a tribal consultant willingly transferred the piece, the museum doesn’t must return an merchandise. But when a tribal officer requests the return of an merchandise, a museum should comply, except it may possibly show it’s a part of the chain of possession, ideally going again to its origin. Complicating issues, hundreds of Native American items on the Met have been in its assortment since 1889, an period when many museums didn’t observe the possession histories of such works.

Questions in regards to the legitimacy of the Met’s possession of art work lengthen past its American wing. As a part of a sweeping investigation into the trafficking of antiquities, the Manhattan district legal professional’s workplace has issued 9 warrants over the previous 5 years to grab about three dozen looted artifacts on the Met, in addition to computer systems, memos and different materials associated to the objects.

In July, brokers seized 21 works valued at $11m from the Metropolitan Museum of Artwork. Over the course of a number of years, dozens of stolen artifacts had been offered as presents or loans by Met donors who later had been flagged for artwork improprieties. They embrace the British antiquities vendor Robin Symes, who in 2006 was linked to a trafficking community and is now reportedly on the run; the gallery proprietor Subhash Kapoor, who was arrested in 2011 in Germany for artwork theft and in 2022 was sentenced in India to 10 years in jail; and the hedge fund founder Michael Steinhardt, who purchased dozens of stolen antiquities that had no provenance and who denied prison wrongdoing, however in 2021 agreed to an unprecedented lifetime ban on buying antiquities to resolve a prison investigation. Steinhardt’s title adorns a Met gallery.

The Met can also be negotiating with the Cambodian authorities over dozens of allegedly stolen items, together with objects donated or offered by the late vendor Douglas AJ Latchford, who labored with a former Met curator.

Matthew Bogdanos, an assistant district legal professional in Manhattan who leads the workplace’s antiquities trafficking unit, stated he and his staff had discovered the gross sales histories of the seized antiquities had been both fraudulent, incomplete or nonexistent. The DA’s workplace checked out submitting expenses for prison possession of stolen property. “However their actions didn’t cross the brink of ‘past an inexpensive doubt,’” Bogdanos advised ProPublica, so no expenses had been filed.

The Met stated in its assertion that it had drafted a brand new Native American Arts Initiative in 2021 underneath the steering of its “first-ever” curator of Native American artwork, Patricia Marroquin Norby (Purépecha, an Indigenous group in Mexico). The initiative, stated the museum, contains “creating an advisory committee and hiring a full-time employees place that can collaboratively give attention to Nagpra obligations and additional prioritize the constructing of ongoing partnerships in addition to the strengthening of group collaborations”. In March, the Met stated it was additionally hiring a Native American artwork researcher whose obligations would come with “some provenance analysis”.

What follows are the tales behind a number of Indigenous items that the Dikers have loaned or given to the Met. ProPublica interviewed specialists and cultural officers on the affiliated tribes to learn the way among the Diker assortment objects survived brutality, theft and exploitation, little of which the guests who pay to see them find out about from the museum.

The 2 carved masks that Beatty was shocked to see on the exhibit’s opening nonetheless dangle within the museum. A description of them on the Met’s web site says that “spirits talk with individuals by whistling: these masks will be the faces of such supernatural beings”.

They could be sacred. However that’s solely a part of the story.

The Alutiit have lived on the Aleutian Islands in south-west Alaska for 7,500 years. In winter, individuals would as soon as huddle indoors and create utensils, garments and ceremonial objects. Utilizing beaver-tooth instruments, they’d carve wooden faces, portray them blue, inexperienced and pink and adorning them with feathers and fur.

At a preordained time, the Alutiit would don their masks and dance and sing in ritual, stated April GL Counceller, director of the Alutiiq Museum & Archaeological Repository in Kodiak, Alaska. A number of the masks’ energy was tied to those that had handed, she stated: “For different ceremonies, the masks had been a strategy to talk with spirit helpers.” After the ceremony, individuals would cover the masks in caves to let the “sky creatures’’ relaxation till the following ceremony.

In 1740, Russians invaded the world for its sea otter fur. They compelled Alutiiq males as younger as 12 to hunt and held Alutiiq girls as ransom. Folks died of hunger, illness and abuse. After a century, the ocean otter inhabitants had almost collapsed, and the Russians left. The US then arrived and arrange faculties that punished Native youngsters for talking their language. By the Eighteen Nineties, the inhabitants of the Alutiit had dropped by 90% to 1,500.

Museums rushed to seize what was left of Alaskan cultures. When a Western Union expedition headed north, the Smithsonian Establishment’s assistant supervisor, Spencer Baird, made positive that 20-year-old William Dall was on board to “salvage” tribal objects. Baird paid Dall $200 a 12 months ($7,000 in in the present day’s {dollars}) to ship his hoard to the museum. Baird additionally used “salvagers” on military expeditions, navy cutters and different quests, buying tens of hundreds of items. The Met obtained Tsimshian rattles and Tlingit reed pipes from donors round this time.

“Nearly every part that wasn’t nailed down or hidden was taken away,” stated Worl, the Sealaska Heritage president.

The Met stated it had offered “up to date summaries to Alaskan Native communities” and “the Tsimshian and different North-west Coast communities are on our listing to obtain new assortment Nagpra summaries”.

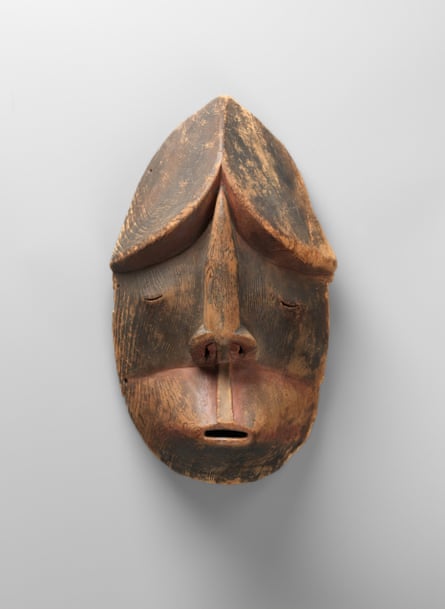

In 1871, 19-year-old Alphonse Pinart of France arrived. He spent months paddling a skin-covered kayak alongside the 600-mile Kodiak archipelago, stopping at islands the place he discovered caves. Inside these caves, Pinart unearthed graves and helped himself to human stays, funeral objects and masks, based on his journals.

That November, he stayed on Kodiak Island and discovered the masks had been utilized in Alutiiq rituals; he bought to observe some ceremonies and revealed a paper about his findings.

After six months, he shipped the masks residence to Pas-de-Calais and left. Earlier than he died in 1911, he donated 87 artifacts to a small museum in a fortress close to Calais. They sat forgotten by the Alutiit for seven generations.

The Met’s provenance solely lists homeowners from the previous 20 years. The Dikers bought the 2 masks in 2003 and donated them to the Met in 2017. The museum filed a abstract with the NPS itemizing them in 2022, 5 years after the deadline.

The museum acknowledged that in 2023, “it was really helpful that the masks stay on view to supply group entry”. Tribal members who dwell the place the masks had been made should journey 3,500 miles to succeed in the New York museum.

In 2019, the Met displayed this bag of arrows with a placard studying: “The painted and beaded patterns on this quiver symbolize protecting sacred powers.”

This description signifies the thing is holy and, out of respect, shouldn’t be displayed, stated Ramon Riley, the cultural useful resource and Nagpra consultant for the White Mountain Apache Tribe in Arizona. “However I must see the paperwork exhibiting how they escaped from their residence,” he stated, that means their provenance.

The Met lists no such historical past. And since the Dikers loaned the quiver set to the Met in 2017 and didn’t switch title to the museum, the Met wasn’t required to tell tribes that it possessed the merchandise.

For the Met to listing the piece merely as “Apache” exhibits a scarcity of due diligence, as there are greater than 10 Apache tribes. If Met curators had contacted any of these tribes, they could have discovered which group created the objects. These items have a historical past that must be revered, stated Riley: “The set might have been looted or taken at gunpoint.”

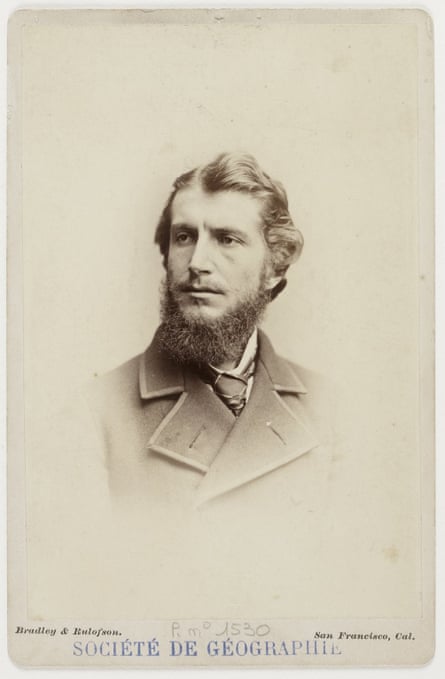

Within the 1870s, one of many extra ruthless leaders in US navy historical past, Gen William Tecumseh Sherman, was pursuing the Apaches. Throughout the civil battle, he had burned Atlanta. As commanding normal of the military and director of the Indian wars, he was utilizing comparable scorched-earth strategies, together with devising the slaughter of 5 million buffalo to starve Native Individuals.

On the time, the US was planning its first world’s honest: the Centennial Worldwide Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia. The Smithsonian was requested to create an Indian “artifact” gallery to rival the antiquities in European museums.

In 1873, the Smithsonian’s director, Joseph Henry, wrote Sherman: “We’re desirous of procuring giant numbers” of Native American “gown, decoration, weapons”. He requested Sherman to inform his troopers to ship “specimens” from the battlefield. At Sherman’s request, Henry paid every uniformed “picker” as much as $500 (the equal of $14,000 in the present day).

The plan helped produce one of many honest’s extra in style reveals, which included Apache arrows. When the expo closed, Henry’s deputy packed the gathering onto 48 rail vehicles certain for Washington DC.

By 1878, the demand for “Indian” objects had grown so giant that the Smithsonian requested the general public to unearth “American Aboriginal” artifacts from mounds, caves and cemeteries. Quickly, the spoils of battle and grave robbing stuffed America’s new museums just like the Met, however few objects had documentation or provenance.

Riley discovered this whereas trying to find the stays of his clan relative. His ancestor labored as a military scout, carrying a government-issued rifle and his personal bow and arrows. However throughout a bloodbath he was arrested for mutiny and hung, stated Riley. The scout was buried along with his possessions. Days later, his physique was dug up and displayed in a cupboard inside Fort Grant, in what was then the Arizona Territory. Finally, his stays had been shipped to the Smithsonian.

Riley doesn’t suppose his relative’s quiver set was displayed by the Met; he believes that the set within the Diker Assortment is a funerary merchandise. “However to individuals just like the Dikers, it’s all artwork,” he stated. “It’s loopy.”

In March, after ProPublica had requested about it, the Met stated it had been made conscious that the quiver-and-arrow set was “doubtlessly culturally delicate” and had eliminated it from public show. The loaned merchandise has not but been returned to the Dikers.

When the Met displayed this merchandise in 2019, the placard learn: “Throughout early reservation life, Plains individuals created objects corresponding to this on the market to visiting navy personnel, authorities officers” and “missionaries”.

“Sale?” stated Peter Gibbs, an archivist within the Rosebud Sioux Tribe’s historic preservation workplace. “The museum has bought it unsuitable.”

What actually occurred is that an “Indian Ring” of brokers and politicians had been taking bribes from individuals who needed to do enterprise on reservations. In 1886, the federal government employed a bankrupt 52-year-old from New York, LF Spencer, as an Indian agent.

Spencer arrived throughout arduous instances on the Rosebud reservation in what’s now South Dakota. The US sought to manage the tribe by sending its youngsters to the infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial college in Pennsylvania, the place they endured harsh labor and abuse, typically resulting in their deaths. The federal government stopped offering rations to folks who refused to surrender their youngsters.

Spencer befriended Noticed Tail Jr, son of Chief Noticed Tail, who held among the tribe’s communal objects, together with the painted tipi. After Noticed Tail died in 1888, Spencer claimed the chief had signed an undated will giving Spencer many objects, together with the “nice drugs pipe of the Sioux nation”.

Gibbs believes the desire is a fraud. The pipe had been handed right down to Noticed Tail by his father and his grandfather. “Junior would by no means have handed this pipe on to Spencer, nor the tipi,” Gibbs stated. Spencer’s dishonesty was so well-known that the Indian Rights Affiliation urged the military to fireside him.

In 1889, Spencer gathered his haul and left. Again in New York, he lectured to parlor golf equipment about his “wild west” exploits, exhibiting off the tipi and different objects.

After Spencer died, his daughter, Harriet Lund, bequeathed a few of his spoils to family and to an unspecified museum. In 1963, Spencer’s granddaughter Vivian Backen offered Noticed Tail’s will and different objects to a Denver artwork vendor, based on Spencer’s descendant Dick Miller. Correspondence between Backen and the Denver artwork vendor helps that historical past.

However the Met’s provenance doesn’t listing these names. The artwork vendor offered a tipi from Spencer’s cache to the Denver Artwork Museum for $500, or about $5,000 in the present day, although it had mildew rot and patched holes.

In 1965, a curator on the museum offered the tipi. The Met’s document says the client was Larry Frank of New Mexico. After Frank died, the Dikers purchased it in 1989. In 2018, they gave it to the Met, the place it was displayed in pristine situation.

The Met has described it as a memento. However Ben Rhodd, the Rosebud Sioux tribe’s then cultural officer, stated it had one other goal fully. The tipi exhibits triumphant warriors on horseback, holding up shields that symbolize their male societies. It was an academic software meant to instill satisfaction in Lakota youngsters for his or her family’ achievements – and to show them the right way to erect a tipi, he stated.

“This inaccuracy is the results of a scarcity of session,” Rhodd advised ProPublica. “And I believe the piece has been looted.”

It’s been 5 years because the Met accepted this present, and tribal officers say they nonetheless haven’t heard from the museum. The merchandise is not on show; the Met stated it intends to contact the tribe and file a abstract as a part of “our ongoing Nagpra work”.

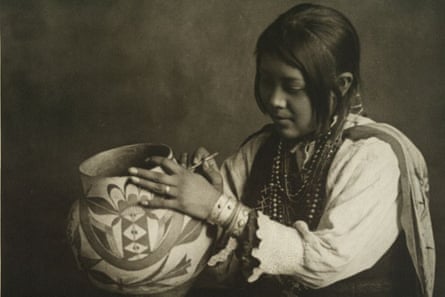

“Nampeyo was the primary south-west potter to grow to be acknowledged by title outdoors her Hopi group and is famend for her technical expertise and aesthetic sensibility,” states the Met’s web site. She was additionally one of many first Native American girls to manage her personal work by promoting on to patrons.

The Met’s historical past of the jar is lacking dates, however there’s sufficient documentation to point out it was in all probability obtained legally. It’s an instance of a industrial murals within the Diker assortment that’s acceptable to show. (In its assertion, the Met stated it “acknowledges the sensitivity of some objects in its historic Native American assortment” and consequently is prioritizing the acquisition of “extra fashionable and modern works by Indigenous artists”.)

In 1874, Nampeyo was a shy 15-year-old who typically wore a standard manta, a sort of scarf. A surveyor snapped her image, which wound up on advertisements to lure vacationers to the Arizona Territory. Unwittingly, Nampeyo grew to become an iconic picture of the south-west.

It was a blended blessing, stated Leigh Kuwanwisiwma, a former Hopi tribal historic preservation officer. For hundreds of years, the Hopi have lived on distant mesas that tower greater than a mile over the encircling panorama, permitting them to freely follow their language, faith and tradition.

Within the Eighties, nonetheless, a flood of dignitaries, artifact “pickers” and students arrived to glimpse the Hopi’s “unique” tradition. Seeing a possibility, an previous soldier from Equipment Carson’s Military brigade, Thomas Keam, arrange a buying and selling submit close to the mesas. He plundered graves and ruins for pots and jars to promote.

An historical Hopi (or Ancestral Pueblo) piece within the Diker Assortment – a Socorro black-on-white storage jar made between 1050 and 1100 – was in all probability looted, based on the late Terry Morgart, a researcher for the Hopi cultural workplace. The jar’s provenance begins about 800 years after it was made, in 1984, when the Dikers purchased it from a gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona.

“Again within the day, males would loot all the great things from a grave and pitch out the human stays,” Morgart stated final 12 months. “Then they’d ship all of it to the museums.”

The Dikers referred ProPublica to the Met for touch upon the bowl.

The museum acknowledged it had not consulted with the Hopi cultural workplace in regards to the historical jar when it acquired it in 2019. In a press release, the museum stated: “In 2022, The Met was in communication on a number of events with the Hopi Cultural Preservation Workplace for steering concerning Hopi objects within the assortment. Any potential points with the Socorro pot weren’t delivered to our consideration at the moment.”

In 1889, Keam offered 3,000 Hopi items to the Smithsonian for $10,000 – or $350,000 in the present day. When Keam ran out of plundered pots, he turned to Hopi girls, together with Nampeyo, to provide them. Her mom was a Tewa, her father a Hopi, and he or she’d grown up close to an deserted historical village. Enjoying with designs, Nampeyo made pots with yellow-orange clay and painted figures on them utilizing black, pink and white mineral pigments. Then she polished the floor to a excessive sheen.

Keam despatched a few of her items to the World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893. Collectors took discover, and Keam offered them her work. In line with some students, Nampeyo acquired a fraction of the income. By the late Eighteen Nineties, she was promoting on to prospects.

An ex-mayor of Chicago, Carter Harrison Jr, acquired certainly one of Nampeyo’s works. The burnt-amber pot had a stylized face of a dancing kachina. Within the Nineteen Thirties, Harrison gave the thing to his males’s membership named the Cliff Dwellers. It sat within the lobby for many years.

The Met’s provenance says the piece was offered in 2010 by Bonhams public sale home. Bidding was intense. When the gavel got here down, the Dikers had purchased it for $350,000, a document for south-west American Indian pottery.

The Dikers gave the jar in 2017 to the Met, the place it’s presently on show. Because it’s not a sacred or funerary merchandise and was made for industrial use, the museum isn’t required to file a Nagpra abstract.

Halfway by the Diker exhibit’s setup and growth, the Met employed some advisers. However this group didn’t have time to contact the suitable tribal officers, stated one of many advisers, Brian Vallo, the then director of the Indian Arts Analysis Middle on the Faculty for Superior Analysis in Santa Fe and a former governor of Acoma Pueblo in New Mexico. Vallo pressured that he was not a tribal chief on the time however stated it was necessary to teach the Met “on problems with cultural sensitivities and illustration”.

(ProPublica spoke to Vallo a number of instances for this story. The Met additionally invited the information group to interview him, describing Vallo as an professional in “Native arts and tradition” and “acquainted with the sphere”.)

This advisory group discovered the Met didn’t have a process for correctly curating, consulting, documenting and displaying Native American objects. They insisted that the museum rent an Indigenous curator.

“The Diker assortment is sort of stunning, however lots of the objects should not nicely documented,” Vallo stated. “There must be an knowledgeable course of that must be adopted so the museum doesn’t absorb objects protected by federal legal guidelines, together with Nagpra.”

Quickly after the Diker exhibit opened on the Met in 2018, O’Loughlin, the Affiliation of American Indian Affairs director, heard complaints in regards to the present from members of her group. She contacted the curator of the Met’s American wing, Sylvia Yount, hoping to attach her with cultural officers of the tribes that had made the objects within the assortment.

“I supplied to carry them to New York so they may give their perspective on the show,” O’Loughlin stated, however Yount declined.

Yount stated publicly that she had consulted with tribal “leaders”. The museum had employed Indigenous and non-Native teachers and consultants – advisers who weren’t chosen by the tribes to symbolize them, as required by Nagpra.

Of the assembly with O’Loughlin, Yount stated in a press release that that they had a “productive” session wherein they mentioned the Met’s “ongoing Nagpra efforts and potential future collaborations.”

As a non-profit with $5.58bn in property, the Met ought to have employed the employees wanted to supply correct details about its works years in the past, specialists stated. “It might set an instance in regards to the significance of combating unlawful commerce and the necessity to shield cultural heritage,” stated Tess Davis, director of Antiquities Coalition, which fights cultural trafficking. “However it appears they’re doing the alternative.”

Tribal members are skeptical of many museums’ willingness to seek the advice of with them. Consequently, the Division of the Inside in January introduced proposals to enhance Nagpra by, amongst different issues, emphasizing that museums ought to seek the advice of with tribes at each step of the method and defer to the customs and information of tribes and their lineal descendants.

When Riley, of the White Mountain Apache Tribe, discovered the Met was displaying the quiver set, he grew upset. “I needed the museum to take it down, however I didn’t know who to ask,” he recalled.

He understood the bounds of Nagpra, having been rebuffed in a earlier try and reclaim “4 of our sacred objects” held by one other east coast museum. “We needed to show that it belongs to us, that it was stolen and that it must be returned. And the museum didn’t must show a factor,” he stated.

And people looted masks? In 2002, Sven Haakanson Jr, then director of the Alutiiq Museum, stumbled upon a few of his individuals’s carvings on the Château-Musée de Boulogne-Sur-Mer in Pas-de-Calais. The French looter Pinart had given the masks to the museum a century earlier. Surprised, Haakanson met the power’s then director and spent the following six years cultivating a relationship with the museum. Lastly, in 2008, the French shipped 34 masks to the Aluttiq Museum as a brief mortgage.

Haakanson mounted a groundbreaking exhibition. “We needed individuals to see that the masks weren’t solely placing, however a part of an Alutiiq custom of sharing 7,000 years of historical past,” he advised ProPublica. The exhibit introduced some individuals to tears. “It helped heal the unstated wounds of the tribe,” he stated.

Now, the Alutiit are relearning the right way to make masks as their ancestors as soon as did.

Such successes encourage Gibbs and the Rosebud Sioux tribe. “There must be a Cultural Repatriation Day when it’s protected for everyone and anyone who has one thing to offer it again to tribes, no questions requested,” he stated.

That features the Dikers, he stated, and the Metropolitan Museum of Artwork.

Trending

-

Bank and Cryptocurrency11 months ago

Cheap Car Insurance Rates Guide to Understanding Your Options, Laws, and Discounts

-

Bank and Cryptocurrency11 months ago

Why Do We Need an Insurance for Our Vehicle?

-

entertainement5 months ago

entertainement5 months agoHOUSE OF FUN DAILY GIFTS

-

WORD NEWS12 months ago

Swan wrangling and ‘steamy trysts’: the weird lives and jobs of the king’s entourage | Monarchy