WORD NEWS

Tim Minchin: ‘Politics impacts my psychological well being … I really feel gaslit’ | Tim Minchin

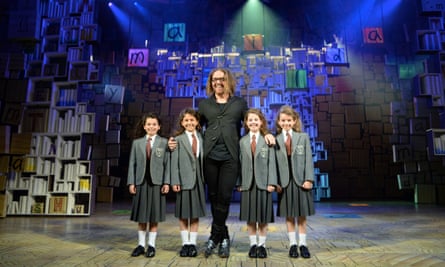

The Australian composer and entertainer Tim Minchin sits exterior a rehearsal room in London. It’s a nice day in April. Tooled up on tea and artistic adrenaline, speaking shortly and properly, the 47-year-old is evaluating the expertise of engaged on two massive stage musicals. In 2010, there was Matilda, the planet-devouring omni-smash, which flourished within the West Finish, on Broadway and on household automobile journeys, reworking Minchin from an anarchic musical comic who may fill a good-sized room on the Edinburgh pageant right into a feted and rich man. “I imply, Matilda, fuck,” is all of the loquacious Minchin can say about that present’s successes for now. Extra attention-grabbing to him, as a result of extra troubled, was the follow-up, Groundhog Day, a 2016 musical tailored from the favored 90s film of the identical title.

“Whenever you make one thing so detailed, over so many hundreds of hours, one thing you suppose is broadly interesting, about how we’re to be as individuals – and it doesn’t fly? That’s extremely painful,” Minchin says.

Dressed as we speak in muted colors, his well-known untidy reddish hair tied again underneath a baseball cap, he lists the little catastrophes that hobbled Groundhog Day seven years in the past: buyers pulling out; the choreographer falling ailing; a sense of being rushed to New York after a robust London opening, earlier than the present was fairly prepared. Groundhog Day closed on Broadway in autumn 2017, after 200-odd performances, and has roughly sat in a drawer since. “It’s not a meritocracy,” Minchin shrugs. “Mamma Mia’s one of many highest-selling musicals ever … Broadway shouldn’t be a measure of what’s good, or to not me. If you wish to go there to make your moolah, then you’ll be able to’t be stunned you probably have a tough journey.”

Fittingly, provided that Groundhog Day is a narrative about do-overs, Minchin and his collaborators will attempt to revive their beleaguered musical on the Outdated Vic in London subsequent month. He’s assured issues will work out higher this time. From contained in the rehearsal room, loud sufficient to growth via a soundproofed door, the brand new forged of Groundhog Day burst into music. They’re being taught the musical’s opening quantity.

“Tomorrow / There shall be solar!” goes the road they’re belting out. Minchin tilts his head. One thing is bugging him and once I ask what, he notes that the actors are singing “too-morrow” as a substitute of “ta-morrow”. Minchin lives in Sydney together with his spouse and two kids. He has flown to London for a fortnight of rehearsals, particularly to pepper the Groundhog Day forged with pedantic corrections. “It needs to be ‘ta-morrow’. Who ever says ‘too-morrow’?”

It isn’t uncommon for artists to include a flamable mix of excessive confidence and low vanity. On this, Minchin conforms to kind: perception by the bucket-load and loads of doubt. However he was skilled on the British comedy circuit. After years in that cauldron, most of what he utters is buried underneath layers of protecting irony. There are micro shifts of tone, eye-widenings, manic grins, flirty pouts, all meant to sign his consistently modulating ranges of seriousness. Minchin is conscious that a few of what he says in interviews comes over badly, his humour generally flattened with out the accompanying efficiency.

He offers an instance. “I may lean ahead to you and say: ‘The difficulty with you, Tom, is that you simply’re clearly a cunt’ … And you’ll hear from the juxtaposition of content material and intent that I really like you.” Now write the C-word down. Now put the C-word in a quote in a newspaper. All of a sudden it reads in a different way. “That’s the issue with the web proper now,” Minchin says, citing a topic – what he sees as the vanity and untruthfulness of progressive politics – that he’ll return to later. “All people clashes up towards one another on-line, pretending irony doesn’t exist. It drives me nuts.”

A luckless Groundhog Day publicist emailed Minchin on the morning of our interview, itemizing what he wasn’t supposed to speak about. Minchin didn’t take properly to that. Simply as with the notes he was handed, the earlier weekend, when he was invited to go on stage on the Royal Albert Corridor and current an Olivier award, Minchin tends to disregard directions on precept. “Many, many individuals have put an enormous quantity of time and money into Groundhog Day. They’re invested in ensuring I toe the road. However that is my job. Speaking about what issues to me is actually my job, whether or not via artwork or by the phrases that come out of my very own mouth.”

Good to listen to, as a result of I need to ask Minchin about one thing sticky. His musical of Matilda remains to be operating in London after greater than 4,000 performances. It was not too long ago made into a film starring Emma Thompson. Minchin has a long-standing, profitable relationship with Roald Dahl’s property, which, latterly, has meant a relationship with Netflix, which purchased the rights to Dahl’s work in 2021. That Netflix deal roughly coincided with a transfer by the youngsters’s writer Puffin to make textual alterations to new editions of Dahl’s books. Sure phrases (outmoded, retro, offensive, innocent: it depended in your perspective) had been edited out.

Within the revised Matilda, as an illustration, Dahl’s slightly abrupt use of “feminine” as a noun was changed with “lady”. A few plot factors had been tweaked, apparently to align the books extra snugly with the 2010 musical and the 2022 film. After an investigation by the Telegraph, and far public protest, Puffin has determined that two variations of Dahl’s books should be printed, one altered, one not. What are Minchin’s ideas on this?

“I made a decision to not wade in,” he says. His diplomacy is so uncharacteristic I merely wait it out.

“I believe I’m unsure,” he says. “And I’m very glad sitting in that house.”

I wait.

“It appears there’s an unimaginable slippery slope downside with enhancing texts. I imply, my preliminary response, once I heard about it? ‘Now we’ll should get all of the rapes out of all of the historical past books. Then the world shall be a greater place.’”

I wait.

“It’s not really about morality. It’s about retaining the property, owned by the Dahls and Netflix, up to date … It’s an attention-grabbing a part of trendy progressivism, that an enormous quantity of change is occurring as a result of firms have recognized the place their bottom-line is finest served.

“Downside one, as I see it? In case you do that as soon as, you’ll should do it to all texts ever, taking out all of the phrases that may upset individuals. Downside two? You’ll have to alter all of it once more in 5 years when the brand new phrases you place in are out of vogue. In order that’s two slippery-slope issues. You’re standing on the high of a double slide. And now you’re spraying cleaning soap on the fucking issues.”

I wait.

“I discover it baffling! I’m perplexed by individuals’s willingness to use concepts that solely work in a single course, as if there aren’t going to be any unhealthy outcomes of this.”

I thank Minchin for his honesty, and I ask him whether or not he would anticipate to get in bother together with his company collaborators for talking so freely.

He winces, as if in actual ache that anybody would suppose so. “Netflix know, and the Dahls know, that I’m not a mouthpiece for them. I could not at all times say the proper issues. However I by no means, ever say what I’m instructed. I don’t owe anybody something. Private-me is agitated by the unsustainable thought of adjusting individuals’s fiction. However my view about that’s solely as vital about your view about that.”

Minchin grew up in Perth on Australia’s west coast, a part of an in depth, socially conservative household. For instance his unthreatening middle-class averageness as a boy, he recounts the primary 20 years of his life at double pace. “My dad and mom had been a stay-at-home mum and a physician. I went to a boys’ college and I did nice. I performed first-team hockey and third-team basketball. I used to be within the college play. I went to school and I did nice. I didn’t take medicine. I married my first girlfriend. I had a job in a ironmongery shop. Then I occurred to get good at … this factor.”

The “factor” was musical comedy. Minchin had initially dreamed of being a rock star, performing via his teenagers and 20s in covers and authentic bands at weddings and cabaret exhibits. Unable to get a report deal, Minchin tried appearing, although not rather more efficiently. Within the early 2000s, newly married to Sarah Gardiner, whom he met at college, and dwelling in Melbourne, Minchin auditioned for an Aussie grocery store chain advert. It could have concerned dressing up as a until receipt. He didn’t get the function. Shortly after, the Minchins moved to London, the place they lived for a few years. “Each time I come again to London now, my agent tells me: ‘Welcome residence.’ I really feel like that is the place I belong. London is the woman I fell in love with however didn’t marry. London is the primary woman who fell in love with me again.”

He arrived within the metropolis in 2002, when, he says, it was nonetheless nearly modern to hit upon stage as if having arrived by chance: no costume, no make-up, no manufacturing values. Attempting to make a reputation for himself, he confirmed up at gigs sporting eyeliner, his hair sprayed, and carrying an inventory of pedantic cues for the stage technician. Drawing on his years enjoying keyboards, he discovered {that a} cabaret-like format suited him. A little bit of piano, a little bit of ranting, bit of private oversharing, music for an encore, accomplished.

Round 2007, when his daughter Violet was born, Minchin wrote a sentimental ballad referred to as White Wine within the Solar, about atheism and the seek for contentment. He began enjoying it to finish his gigs. He typically ranted about organised faith from the stage, and audiences appeared to understand this softer finale. Minchin was performing in London one evening when the director Matthew Warchus got here to look at. It was 2009. Warchus was on the lookout for a composer for a germinating Matilda musical. White Wine within the Solar, which frequently left individuals in tears, was the clincher. Warchus introduced alongside a collaborator, the playwright Dennis Kelly, to see Minchin, too.

Quickly the trio had been in dialogue about how Matilda may work on stage, in music. “I by no means reread Dahl’s e book,” Minchin tells me now, “I by no means watched the [1996] film.” As an alternative, in typical trend, his opening chat with Warchus and Kelly contained a rant. “In case you get another person,” Minchin concluded, “don’t allow them to fuck this up.” A 12 months later, in 2010, the trio had been collectively at Matilda’s press evening in Stratford-upon-Avon, about to get 5 stars from just about each critic there, about to start a flawless run of glory that would come with excursions, transfers, Tonys and Oliviers.

Minchin’s post-interval quantity Once I Develop Up shortly established itself as a musical-theatre all-timer, on a degree with Sondheim’s Being Alive or Lerner and Loewe’s On the Avenue The place You Dwell – a music that does nearly nothing, plot-wise, however that leaves the viewers achy and elated. The recognition of Matilda supercharged Minchin’s performing profession, in tandem. He bought a component within the TV present Californication and performed Judas in a 2012 revival of Jesus Christ: Famous person.

After that, Minchin took time without work to focus on writing. He and Sarah had their second little one, Caspar, and moved to Los Angeles, the place Minchin signed a take care of DreamWorks to make an animated characteristic movie. Collaborating once more with Warchus and different members of the Matilda crew, he wrote the music and lyrics for Groundhog Day, which received five-star critiques, one other Olivier and moved in 2017 from the Outdated Vic to Broadway, the place it was much less fondly obtained. That 12 months, DreamWorks abruptly cancelled Minchin’s characteristic movie, Larrikins, after the corporate was purchased by Common, and, in Minchin’s account, made it too expensive for one more studio to accumulate. (He has spoken about being instructed this excessive value was “schmuck insurance coverage” – the value of not being made to seem like a schmuck if one other firm made it into a success.) 4 years of labor, he says, nixed.

“I couldn’t be extra affirmed,” Minchin says. “1000’s and hundreds of messages from individuals who love my stuff. And I don’t undervalue that. However you simply get used to it.” He means, every time a post-Matilda venture has stuttered, the lingering glow of Matilda has not afforded a lot safety. “It’s, like, oh, your $100m movie bought shut down? Properly you went to Hollywood, mate! It’s not a craft honest over there. Dropping a film shouldn’t be actually grief. However having time taken away from you? You grieve that,” he says. “It put me in a extremely unfavorable house, one I needed to write my manner out of.”

The household moved again to Australia. To recover from the DreamWorks disappointment, Minchin created a surreal TV present a couple of pair of misfits, Upright. “I’m gratified by Upright. It’s 8.4 on IMDb. It’s received awards. However fucking nobody’s seen it. And that’s a bit unhappy.” These experiences of damp squibs or flops have taught him that doing the job is what counts; creation, not reception. “It’s at all times a little bit of an anticlimax to place one thing new into the world. You’re, like, ‘It’s accomplished! All people favored it! Or no person favored it! I suppose I’ll simply maintain going?’”

After all, it’s simpler to maintain going when you’ve the financial institution of Matilda issuing dividends. The 2022 film may have made Minchin even wealthier, with out him having to try this rather more than mutter encouragement to the director, Warchus.

Er, I say to Minchin … can we discuss concerning the Matilda loot?

“Brits don’t speak about that, do they? Cash?”

He smiles. What can he inform me? “I believe my retirement’s in all probability OK. Until the concepts in Matilda grow to be cancellable. There are some in there! I’ve heard individuals say that the road ‘Solely you’ll be able to change your story’ [from the song Naughty] is like blaming the sufferer. Proudly owning your personal destiny is untrendy.”

Do any of Matilda’s lyrics, written by thirtysomething Tim, make fortysomething Tim wince?

“There are a pair the place I believe, ‘Shit! I used to be enjoying fast-and-loose there.’ And there are lyrics I’ve modified, as an illustration the phrase ‘midget’. I by no means considered that phrase as a slur. I considered it as a phrase for a small factor, a midget submarine, a midget plant … What you need to do shouldn’t be harm anybody. However as an artist – or as an individual in life – it’s important to perceive that you simply are going to generally harm individuals.”

The music Revolting Kids from Matilda expresses Minchin’s worldview fairly properly. His lyrics play on the phrase revolt: to insurgent, and to appal. Minchin is eager on mutiny, even the place which means inflicting offence. In his comedy-cabaret days, he typically attacked what he noticed because the illogic of non secular religion. In 2016, Minchin debuted a music about Cardinal Pell, the late Australian priest who had figured in a number of little one sexual abuse scandals. It has been considered 4m occasions on YouTube. In all this revolting, Minchin was cheered on by the liberal progressives of his core viewers.

Nevertheless, Minchin has discovered himself out of step with facets of his personal politics. When he speaks about making geographic relocations, he says: “There’s one thing essentially troublesome about not understanding the place house is.” I sense he not is aware of the place his political house is. And this unnerves him. Repeatedly as we discuss, Minchin returns to the topic of contemporary progressivism and his gradual unmooring from it. “I maintain watching liberals assert stuff. And there’s this backfire impact. There are unintended penalties to the pushing-through of our beliefs.

“What I’m anxious about is that in our makes an attempt to push ahead social justice we’re shedding individuals. We’re insisting individuals catch up in a short time. And once they fail to, they discover themselves in opposition. In case you inform those who they’ve to return on board in a short time with new concepts of social justice, and also you don’t seduce them, for those who merely demand it, it doesn’t work. They’re gonna search for one other narrative. They’re gonna search for somebody who makes them really feel all proper for not being on board with that shit … So a Trump comes alongside, and finds success by saying, ‘I offer you permission to fuck all that off.’”

Minchin removes his cap and pushes again his hair. He does this a number of occasions, a gesture of mounting frustration. “The place I believe politics impacts my psychological well being is that I really feel gaslit. It seems like everybody’s playacting. On the proper, it’s the playacting of pretending you’re not rich, the ‘frequent man’ stuff, the skullduggery of that. And on the left, it’s the concept that all of us carry out this self-protecting model [of politics] on social media, then go residence, have dinner, and roll our eyes … I’ve been accused of drifting proper. However, it’s like, maintain on! I’ve spent my complete profession criticising illogic. I really feel like I’m nonetheless doing that, besides that the faith I now see an issue with is id fundamentalism. I really feel like that is extra damaging than monotheism. I don’t suppose my values have modified.”

Whoever does suppose their values have modified? From inside our personal heads, it at all times seems to be as if the surroundings is shifting, not us. I sketch out for Minchin my idea about political righteousness. Liberals, lengthy used to the comfy excessive of supposing they had been on the proper aspect of historical past, bought hooked on that drug, and are actually struggling the consequences of its withdrawal. Youthful liberals may simply have minimize off their provide.

Minchin nods. “Folks underneath 30 have at all times been extremely passionate,” he says. “And so they’ve at all times been somewhat bit dumb. Underneath 30? You’re passionate however you don’t really know fairly sufficient. Now we’ve made a mode of communication the place these individuals have an enormous quantity of energy, to have individuals lose their jobs or no matter. And as a 47-year-old, principally what I see is immaturity with a gun.”

Isn’t that what Minchin practised, as a younger comic?

“Immaturity with a microphone,” he nods, “yeah.”

The Groundhog Day rehearsal has resumed. Morning is about to hit on that fateful Groundhog Day in small-town America. Regular ahead progress is about to be disrupted and, to seize this, Minchin has organized his music in order that the forged all get lodged on a observe. As an alternative of singing “If not tomorrow / Maybe the day after”, they sing “If not tomorrow / Maybe the day aaaaarrrgh”. The ultimate observe begins to sound like an anguished howl.

Minchin is aware of he can not management political winds, not as we speak and never the day aaaaarrrgh both. Watching his youngsters grow to be younger adults, watching them develop passions of their very own, has helped him settle for this. “What my youngsters have taught me is humility about your management over shit. When my youngsters had been small, I assumed they had been clean slates, or issues to be moulded. The truth is, all you do as a dad or mum is bear witness to their emergence. It’s lovely.”

His youngsters are youngsters now. They generally get issues incorrect. Minchin is sort of 50. He generally get issues incorrect, too. He says: “We attempt to get issues incorrect collectively.” It’s in all probability one of the best that any of us can do.

Trending

-

Bank and Cryptocurrency11 months ago

Cheap Car Insurance Rates Guide to Understanding Your Options, Laws, and Discounts

-

Bank and Cryptocurrency11 months ago

Why Do We Need an Insurance for Our Vehicle?

-

entertainement5 months ago

entertainement5 months agoHOUSE OF FUN DAILY GIFTS

-

WORD NEWS12 months ago

Swan wrangling and ‘steamy trysts’: the weird lives and jobs of the king’s entourage | Monarchy